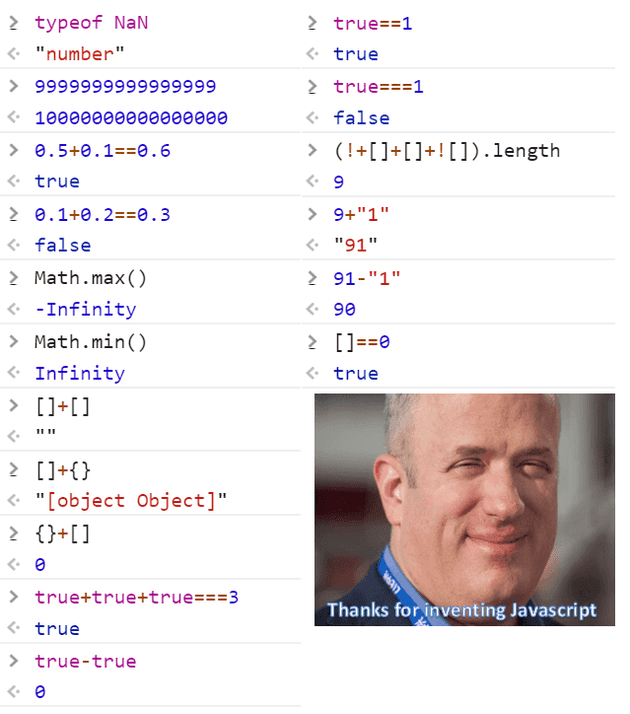

If you search for javascript memes in google, there will be 296.000.000 results and many of them are about corner cases in this language like the meme above. Those corner cases are weird, unpredictable and should be avoided, only when we do not know how javascript works and what’s going under the hood. When we encounter such confusions, it’s easier to make meme of them and blame the language than blaming ourself for our lack of understanding of the tool, which we use everyday. I used to be that type of developer until i saw the book series You don’t know js of Kyle Simpson on github a few years ago. It completely changed my mind. After spending years poring over the series and watching Kyle’s courses, it turned out I didn’t know Javascript as much as i thought. On my journey to understand javascript better, i really want to note down the knowledge and the experience i gained and this series is the beginning of that adventure.

In order to get a better grip of javascript, let’s take a look into its core, which according to Kyle, can be divided into 3 pillars:

- Types

- Scope

- Object and classes

In this blog, we’ll go into the first pillar: Types

Built-in types

One thing we should make clear before diving into types: Variables don’t have types, but the values held by them do. There are 7 built-in primitive types in javascript: null, undefined, boolean, number, string, object, symbol. Operator typeof can be used to identify them

console.log(typeof null); // "object"; 😩

console.log(typeof undefined); // "undefined";

console.log(typeof true); // "boolean";

console.log(typeof 25); // "number";

console.log(typeof 'Khanh'); // "string";

console.log(typeof { name: 'Khanh' }); // "object";

console.log(typeof Symbol()); // "symbol";the typeof operator will return a string representing the value’s type, surprisingly except for null type. This bug this feature stands from the very first implementation of javascript.

undefined vs undeclared

It’s tempting to think undefined and undeclared are synonyms and those terms can be used interchangeably but in fact, they are 2 different concepts. An undefined variable is one that is already declared, is accessible in scope, but has currently no value. By contrast, undeclared is one that is not declared, not accessible in the scope. When we try to use undeclared variable, the ReferenceError will be thrown

const undefinedVar;

undefinedVar; // undefined

undeclaredVar; // ReferenceError: undeclaredVar is not definedType coercion

Coercion aka ‘type conversion’ is a mechanism of converting one type to another. There are two types of coercion: “implicit” and “explicit”. Here is an example of coercion taken from You don’t know js.

var a = 42;

var b = a + ''; // implicit coercion

var c = String(a); // explicit coercionHow does coercion work internally and what’s going under the hood? In order to know the internal procedures, we need to understand abstract operations.

Abstract operations

Every time a coercion happens, it’s handled by one or more abstract operation. They are internal-only operations and not like a function that could somehow be called. Here we will look into 3 abstract operations: ToPrimitive, ToString and ToNumber. There are more operations to refer and use, you can check the spec for more information

ToPrimitive

If we have something non-primitive (array, object,…) and want to make it into primitive, ToPrimitive is the first abstract operation involving in. The operation takes 2 argument: input and the optional preferredType (hint), which can be either string or number. All built-in types except for object are primitives, so every non-primitive has 2 available methods derived from Object.prototype: toString() and valueOf(). If the hint is string, toString() is invoked first. If the result is primitive value, valueOf will come into play and vice versa if the hint is number.

| hint: “string” | hint: “number” |

|---|---|

| toString() | valueOf() |

| valueOf() | toString() |

ToPrimitive is inherently recursive, that means if the result of the operation is not primitive, the operation will be invoked again until the result is primitive.

ToString

Don’t get confused with

ToStringandObject.prototype.toString(), they are 2 different things.ToStringis an abstract operation, an internal operation, meanwhile,Object.prototype.toString()is a function derived fromObject.prototypeand available to all objects in javascript.

The coercion of non-string value to string is handled by ToString operation. It converts the value according to this table and here are some examples:

undefined -> 'undefined'

null -> 'null'

true -> 'true'

15 -> '15'For non-primitive values, ToPrimitive will be called with hint string, which in turn invoke the Object.prototype.toString() and then valueOf() (if necessary). The default implementation of Object.prototype.toString() returns [Object object]. Array itself has an overridden implementation for toString(): It removes the square brackets and concatenate array element with ,. This can lead to some weird interesting results.

[] -> "" 🤔

[1, 2, 3] -> "1, 2, 3"

[null, undefined] -> "," 😳

[,,,] -> ",,,"ToNumber

The operation converts a non-numeric value to a number according to this table. For non-primitive values, ToPrimitive will be called with hint number, which in turn invoke the valueOf() and then Object.prototype.toString() (if necessary). Because the default valueOf() returns the object itself. Let’s take an example to understand the operation better:

[""] -> 0- Because

[""]is not a primitive value, theToPrimitive()will be invoked with hint number - The

valueOf()will be invoked, which returns the object itself. The result fromvalueOf()is not a primitive value so theObject.prototype.toString()will come into play. - The overridden implementation of array’s

toString()removes the square bracket and concatenate array’s element with,, so[""].toString()returns"". - Look up the table i mentioned above, the empty string will be converted into 0.

Cases of coercion

With those abstraction operations as foundation, it’s time to tackle the topic of coercion. Is type coercion really an evil and a horrible part, that we should avoid? You can claim to avoid coercion because it’s corrupt but in some cases, coercion is really helpful or you may have used it without knowing about it.

const age = 29;

console.log(`My brother is ${age} years old`}; // "My brother 25 years old"How on earth can javascript concatenate the string “My brother is” to age, whose value is currently a number? Yeah, you’re right, it’s type coercion. Without type coercion, you need to convert the age explicitly like this:

const age = 29;

console.log(`My brother is ${String(age)} years old`};

// "My brother 25 years old"

// OR

const age = 29;

console.log(`My brother is ${age.toString()} years old`}; // "My brother 25 years old"Of course, the first version is always my preference because of its conciseness and readability.

Another example of type coercion that you should have seen in many code bases as working with browsers:

function addNumber() {

return +document.getElementById('number').value + 1;

}Or there’s a if statement using type coercion, that every js developer should have written:

if (document.getElementById('number').value) {

console.log("Oh, that's having a value");

}Assemble our knowledge

After knowing some abstract operations and how it works, now we should be able to explain some of corner cases in the above meme. Let’s go through some of it

[] + [] -> ""

The result of ToString() with empty array is “”, so "" concatenating with "" of course returns “”

[] + {} -> "[Object object]"

It should be an easy one. [] is converted to "" and the default Object.prototype.toString() returns "[Object object]", so the result if of course string “[Object object]”

{} + [] -> 0

Hm, that’s really a tricky one. Since curly braces at the beginning of a statement are interpreted as starting of code block, the first pair of curly brackets is interpreted as an empty code block. So this expression is equivalent to:

+[] // The plus here is an unary operator, which converts [] to number

ToNumber([]) // calls toPrimitive with hint number

ToPrimitive([], 'number') // calls valueOf() first and then toString() if necessary

// [].valueOf() returns [], which is not primitive, so we have to use toString()

Number([].toString())

Number("") -> 0

true + true + true = 3

The plus here is a binary operator, so true will be converted into number 1, please refer to the table i mentioned in ToNumber. So yes, true + true + true is really 3 in javascript.

(! + [] + [] + ![]).length = 9

The first exclamation mark performs a boolean coercion, the first unary plus operator handles a numeric coercion. So the first three symbols !+[] will perform firstly a numeric conversion of an empty array, and then convert that result to a boolean value. The second [] will be converted into primitive like the way i explained in previous examples, and the last [] is converted to boolean with [ToBoolean abstract operation](https://tc39.es/ecma262/multipage/abstract-operations.html#sec-toboolean), which i don’t mention in this blog. So this expression is equivalent to

(!Number([].toString()) + [].toString() + false)

.length(!Number('') + '' + false)

.length(!0 + 'false')

.length(true + 'false').length;

'truefalse'.length = 9;Summary

In this post, we turn our attention to the types systems and how type conversions in javascript works. The implicit type coercion in javascript is handled by abstract operations. Dynamic types is one of JS’s core features but on the other hand, it’s also controversial. In order to end this post, I’d like to take a quote of Kyle Simpson from his famous series You don’t know JS

Coercion gets a bad rap, but it’s actually quite useful in many cases. An important task for the responsible JS developer is to take the time to learn all the ins and outs of coercion to decide which parts will help improve their code, and which parts they really should avoid.